Fascism is a tricky term to define. One of the issues with many existing definitions of fascism is that they tend to focus on surface-level features, including aspects of fascist ideology, psychology, or culture, without analyzing the class composition of fascist movements, or the historical and material factors that lead to their emergence and growth. Without an understanding of its historical roots, fascism appears as a kind of anomaly, a spontaneous mass delusion that can’t be understood by any rational means. This makes it not only impossible to predict when and where fascist movements will arise, but also very difficult to fight back, since we may know what fascists believe but not how they came to believe those things. Even knowing who is likely to join a fascist movement becomes difficult, since participation is framed purely as a matter of an individual’s psychology or state of mind. This involvement also tends to be seen in black and white terms: either you are a fascist, or you’re not, foreclosing any exploration of the various factors, forces, and groups that contribute to the growth and development of fascism. This is why it’s important to see fascism as a movement, made up of a wide variety of actors with different interests and different levels of commitment to fascist beliefs, rather than a disembodied collection of ideas, values, or temperaments. While fascism may seem incomprehensible to the liberal mainstream, it is very much a flesh and blood phenomenon for those fighting it in the streets, online, at their workplace, or wherever else it happens to emerge, and this needs to be taken into account if resistance is going to be effective.1

To develop a clearer picture of how fascism has been discussed historically, and how it’s broadly understood today, I’ll be providing a brief overview of a selection of influential texts that either attempt to explain fascism directly, or explore contemporary fascistic movements without necessarily making the connection to older forms of fascist organizing. These various accounts of fascism can, I would argue, be classified into two broad categories: idealist definitions that focus largely on the culture, ideas, and psychology of fascism, and materialist definitions that explain fascism in terms of the material conditions and interests that give rise to it, often emphasizing the role played by capitalism and/or imperialism. Despite my criticisms of the former, I’ve included both in the hopes of fostering a more holistic understanding of fascism which refuses to simply take fascists at their word or to dehistoricize fascist movements, while still paying attention to how they present themselves to the world and the various types of recruitment strategies they use to grow their numbers during periods of crisis.

Idealist definitions

Umberto Eco: Ur-Fascism

Umberto Eco’s essay “Ur-Fascism” attempts to explain fascism in terms of “a way of thinking and feeling, a group of cultural habits, of obscure instincts and unfathomable drives.” On the one hand, Eco acknowledges the “fuzziness” of fascism, the fact that its public face, its organizational structure, and the expressed ideas of its proponents varies from one historical period or location to another. At the same time, he insists that it is possible to come up with a comprehensive list of features that, together, define what he calls “ur-fascism.” These features include:

1) The Cult of Tradition: The development of a culture based on a combination of different beliefs and practices, regardless of contradictions, which is held up as the ultimate source of truth, rendering the advancement of learning impossible

2) The Rejection of Modernism: a rejection of the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment as the source of “modern depravity,” which does not include a rejection of technology or industrial production

3) The Cult of Action for Action’s Sake: Action is seen as beautiful in and of itself, and prior reflection is discouraged, while intellectuals are framed as degenerate snobs who reject tradition, encouraging distrust of the liberal intelligentsia

4) Disagreement is Treason: Analytical criticism is attacked because it threatens to expose the contradictions required for fascist ideology

5) Fear of Difference: Fascism exploits a “natural fear of difference,” and rejects intruders

6) Appeal to a Frustrated Middle Class: As a result of an economic crisis, the middle class suffers from “feelings of political humiliation,” and fears pressure from the lower social classes, creating a mass audience for fascism

7) Obsession with a Plot: Fascism weaves the fear of difference into a plot, leading its followers to feel besieged, and cultivating xenophobia and nationalism

8) The Enemies are Too Strong and Too Weak: The enemy is alternately presented as incredibly strong, in order to stir up feelings of humiliation and resentment, and incredibly weak, in order to promote confidence and a sense of superiority

9) Pacifism is Trafficking With the Enemy, Life is Permanent Warfare: Fascism depends on a state of perpetual war, creating a predicament where a final victory that would lead to peace is simultaneously sought after and rejected

10) Contempt for the Weak: All citizens of the nation are considered superior by nature, yet society is structured hierarchically, so that every group despises its inferiors, creating a form of popular elitism

11) Everybody is Educated to Become a Hero: Heroism is the norm, and followers are taught to crave a heroic death, tying the cult of heroism to the cult of death

12) Machismo: The desire for heroism is displaced onto sex, fostering machismo and a disdain for women, which is then further displaced onto weapons (as phallus and symbol of masculinity)

13) Selective Populism: Citizens are called upon to play the role of the People, which is conceived of as a monolithic entity with a singular will, to be “interpreted” (i.e. dictated) by the Leader

14) “Newspeak”: Discourse is limited to a simple vocabulary and syntax that limits the tools for critical thinking

While Eco’s text does help to break down many different elements of fascist ideology, his list does not allow us to explain why fascism grows in some periods and not others. For example, in point five, he mentions fear of difference, but does not examine where that fear comes from or how it is promoted within a population. Instead he describes it as “natural,” ignoring the role that the media, the education system, the criminal justice system, the military, and other institutions play in spreading and instilling fear of the “Other,” long before fascist movements ever come to power. By evading the question of where fascism comes from, Eco downplays the extent to which fascism’s roots lie within our own society, and the institutions of liberal democracy.

Angela Nagle: Kill All Normies

Angela Nagle’s book Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right, has been widely hailed as one of the most important accounts of the Alt-Right released to date. The book has also received its fair share of criticism, particularly from those farther to the Left. Like Eco, Nagle tends to focus on surface-level dynamics while paying little attention to underlying structural issues. Nagle looks at the development of internet culture and the emergence of the Alt-Right and sees only “a response to a response to a response.” Although it’s true that both the Left and the Right do respond and adapt to the tactics, strategies, and rhetoric deployed by their rivals, she misleadingly implies that the rise of the Alt-Right can be attributed simply to the prominence of their ideological opponents, namely Tumblr feminism and liberal “political correctness,” as opposed to a more fundamental shift in social and material conditions.

Although Nagle begins with Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign, she fails to mention the economic crisis, or the long recession that followed as potential factors in the growth of reactionary forces. She also avoids making any direct connection to fascism, instead preferring to take the Alt-Right at their word when they refer to themselves as an ideology that “supersedes liberal democracy, Marxism and fascism,” presenting them as a rising form of counterculture that is fundamentally anti-establishment. The fact that they have received, in many cases, funding and political backing from the establishment they claim to oppose does not seem to bother Nagle, as she takes this more as a sign that the Alt-Right is winning through its own inherent strengths, than a sign that they may be far less “countercultural” than they claim to be. Nagle argues that “the Alt-Right is, to varying degrees, preoccupied with IQ, European demographic and civilizational decline, cultural decadence, cultural Marxism, anti-egalitarianism and Islamification but most importantly, as the name suggests, with creating an alternative to the right-wing conservative establishment,” however this alternative has proven to be less a radical departure than an intensification of various existing (and sometimes contradictory) beliefs.

Despite its shortcomings, Nagle’s book does provide a convenient introduction to some of the major currents and factions that exist within the Alt-Right, including the misogynistic manosphere, the anime-loving trolls of 4chan, the tech-fetishizing neo-reactionaries of the Dark Enlightenment, and white nationalist “intellectuals” like Richard Spencer. She also discusses “alt-light” figures like Milo Yiannopolous, who flirt with the Alt-Right and participate in pushing their views into the mainstream, while keeping just enough distance to maintain plausible deniability. For Nagle, the main thing that unites these disparate groups is their hatred of the Left and “PC culture,” a spirit of transgression, as well as their rejection of the “conservative establishment.”

But while it’s clear that the image of rebellion is an important part of the Alt-Right’s appeal, the white supremacist, misogynistic, transphobic, ableist core of the Alt-Right is very much a product of the institutions they are supposedly rebelling against. As J. Moufawad-Paul aptly puts it:

The reason why people gravitate towards the Alt-Right is not because of the behaviour of leftists but because, primarily, racism is an organic option for a white male who has been taught to see any reform (no matter how paltry) [aimed] at creating a level playing field as a personal attack. These are people who do not like being told that they cannot be in control of everything, whose white identity is fragile when subjected to critique, and who thus seek to reinvigorate a sense of power by submerging themselves in a current that never went away in a colonial and imperialist social formation: white supremacy.

J. Moufawad-Paul, “The Alt-Right Was Not A Response To Some ‘Alt-Left’,” July 24, 2017.

In a similar vein, the victim-blaming rape culture and misogyny that pervades the “manosphere,” is a reflection of a society structured around the oppression of women. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, patriarchy has been integral to the survival of capitalism, which relied on forcing women, often through threats of violence, into a subordinate role in order to suppress wages, keep the working class divided, and ensure high birth rates to keep up with capitalist expansion. As Parenti notes:

The patriarchy buttressed the plutocracy: If women get out of line, what will happen to the family? And if the family goes, the entire social structure is threatened. What then will happen to the state and the dominant class’s authority, privileges, and wealth? The Nazis were big on what we would today call family values—though most of the top Nazi leaders could hardly be described as devoted family men.

Parenti, Blackshirts and Reds: Rational Fascism and the Overthrow of Communism (City Lights Books: San Francisco, 1997), 16.

Although maintaining a steady supply of babies is no longer such a pressing issue,2 keeping women down while providing certain privileges to men is still useful not only to the capitalist class, but to the many men who benefit from this relationship. The idea that women are inferior to men, that they are naturally suited to domestic labour, and that they are to some extent the sexual slaves and property of men may have largely fallen out of the realm of polite conversation (thanks to centuries of collective struggle), but they remain a part of the cultural undercurrent, reinforced in countless different ways through the workings of institutions that maintain the gender binary and accord more credibility and worth to men than women.

Prominent figures associated with the Alt-Right, including pick-up artists like Daryush Valizadeh (aka Roosh V), white nationalists like Richard Spencer, and neo-Nazi hackers like Andrew Auernheimer (aka weev), have simply absorbed elements of the dominant culture and taken them to their logical conclusion. This in itself is a type of taboo, as the liberal establishment would prefer to keep the brutality and violence of the system hidden, in order to maintain a kind of false peace, where portions of the population can continue to believe that they live in a fair, just, and “civilized” society. In this sense Nagle is correct that the Alt-Right is a reaction to liberalism, but it is also a product of its contradictions. The Alt-Right and Trump are “dangerous” only insofar as they expose the cracks in the system, making it clear that racism, sexism, and other forms of targeted violence have not disappeared altogether, as some would have us believe.

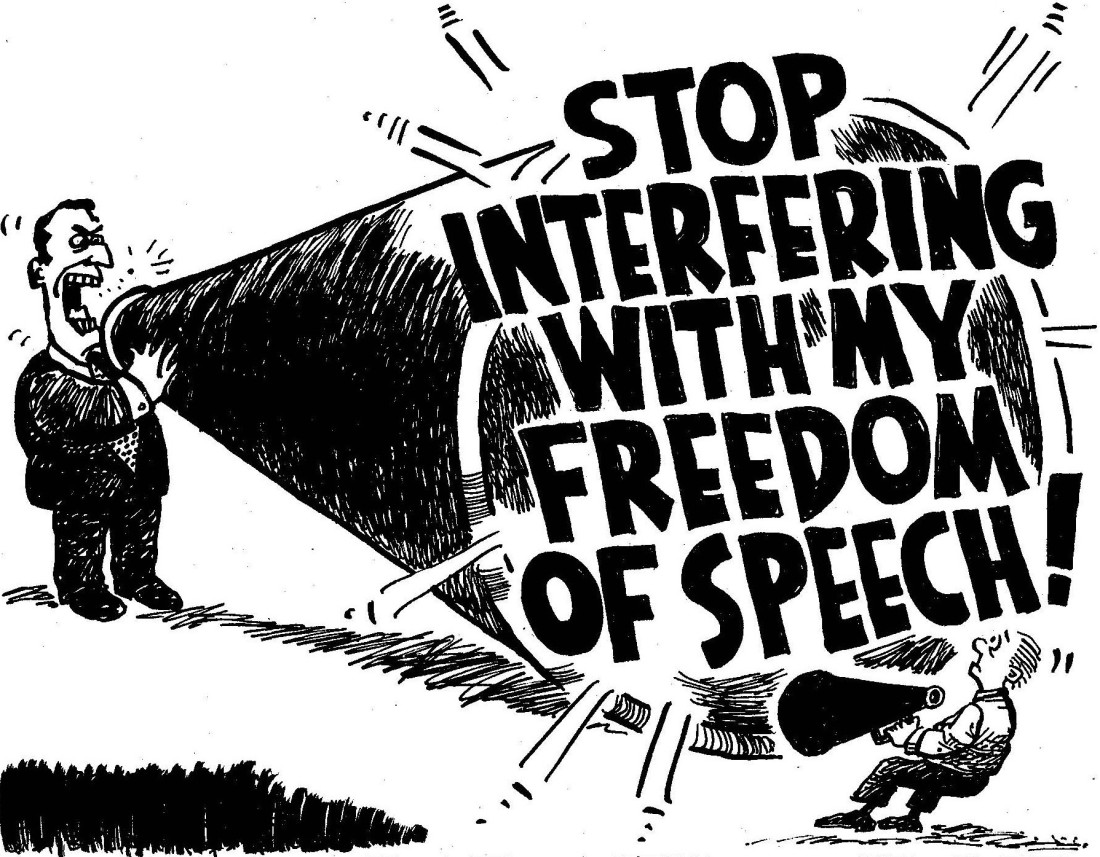

The appearance of transgression is further amplified by the Alt-Right’s habit of appropriating the surface-level imagery of the Left to appeal to a broader audience, whether that’s the remixing of communist propaganda by GamerGate, or the strategic use of appeals to “free speech.” Nagle’s account highlights what happens when the language and aesthetics of leftism becomes unmoored from its political foundations, allowing it to be more easily co-opted and deployed by the Right. Transgression against the status quo can mean anything and nothing when you refuse to define what you mean by the status quo. The result is a pleasurable power fantasy that offers release from social pressures and internalized norms, but without any sense of responsibility to others.

Far from being new, however, this process has happened repeatedly throughout the history of fascism, with many fascist movements making vague or explicit references to socialism early on in an attempt to grow their base, while rejecting the underlying political goals and analysis. This does not mean, however, that the political movements they were appropriating from were invalid or somehow aligned with the politics of the Right, as Nagle seems to imply. By failing to connect the Alt-Right to the history of fascism and white nationalism more generally, Nagle misses out on the many ways in which the Alt-Right is a continuation of historical patterns, as well a recombination of existing elements into a form that is at once new and yet intimately familiar.

As Jordy Cummings argues, Nagle’s book also ends up reinforcing a politics of exclusion, punching left just as often as it punches right. From Nagle’s point of view, the Alt-Right would not exist if it were not for the left going too far with their “hysterical” callouts and their “anti-male, anti-white, anti-straight, anti-cis rhetoric.” At times she veers towards what is now commonly called “horseshoe theory,” which equates the Far Left with the Far Right by framing both in terms of their distance from the (reasonable, rational) political centre. In contrast to theories which position the Left and Right as polar opposites, horseshoe theory portrays the political spectrum as a horseshoe, highlighting the supposed similarities between the two “extreme” ends of the spectrum, which are assumed to be equally dangerous. The result is that Nagle ends up pinning much of the blame for right-wing violence on the very people who are being targeted.

Hannah Arendt: The Origins of Totalitarianism

Arendt’s book The Origins of Totalitarianism is often cited in relation to fascism, and in many ways helped set a precedent for the arguments put forth by Nagle. While the book tackles a wide variety of topics, including anti-Semitism, imperialism, and the origins of racism, the part which tends to attract the most attention is the final section on totalitarianism. Writing in the wake of World War II and during the early years of the Cold War, Arendt applies the horseshoe theory described above to Bolshevism and Nazism. This is particularly evident in the final section of her book, where she argues that they are both examples of mass movements that led to the establishment of a totalitarian regime. Arendt describes totalitarianism as a form of absolute evil, characterized primarily by the arbitrary, unrestrained use of violence and terror, deployed even in the absence of any real opposition or threat. Totalitarianism is a purely destructive phenomenon, detached from profit motives or rational self-interest, and has its origins in mass movements composed largely of “neutral, politically indifferent people who never join a party and hardly ever go to the polls.” These masses, she claims, lack any common social, political or economic interest, and emerge from atomization and the breakdown of bourgeois-dominated class society. The only thing that ties them together is a set of convictions or sentiments which, she argues, are shared by “all classes of society,” including anger and cynicism towards existing political parties, the feeling of being disposable, and the radical loss of self-interest.

For Arendt, it makes little difference whether these masses are organized by communists or by fascists, as both cases ultimately lead to the same horrific conclusion. In this sense, her account aligns quite well with the anti-communist political climate of the Second Red Scare, which coincided with the publication of The Origins of Totalitarianism, and may have accounted, in large part, for its popularity. Arendt provided an intellectual argument for stripping communism and fascism of their distinct political characteristics, and uniting them under the banner of a single, mass pathology. In doing so, she contributed to the demonization of communists, while also legitimizing the more general fear of democracy and mass organizing that underlies liberal elitism. For Arendt the masses are inherently dangerous, and must, for their own good, be restrained by a society governed by educated elites and state institutions. As Corey Robin points out,

Arendt’s account dissolves conflicts of power, interest and ideas in a bath of psychological analysis, allowing her readers to evade difficult questions of politics and economics. We need not probe the content of a particular ideology – what matters is not what it says but what it does – or the interests it serves (they do not exist). We can ignore the distribution of power: in mass society, there is only a desert of anomie. We can disregard statements of grievance: they only conceal a deeper vein of psychic discontent.

Corey Robin, “Dragon-Slayers,” London Review of Books, 29, no. 1 (January 4, 2007): 18-20.

This refusal to acknowledge the role that class or material interests play in creating and cultivating fascism places Arendt in direct opposition to materialist accounts of fascism, which argue that fascist groups are based in the middle class, and gain power thanks to the cooperation of the capitalist class. The middle class turns to fascism in order to preserve its own position in society and avoid being pushed down into the ranks of the working poor, while the capitalist class attempts to use fascist movements to crush working class rebellion and maintain their position of power. Fascism is therefore a perfectly rational, if short-sighted response to capitalist crisis, one which operates in favour of the powerful and against the interests of the oppressed. Communism, on the other hand, presents the greatest threat to the interests of the capitalist class and all the various, interwoven structures of power (such as patriarchy and white supremacy) that allow capitalists to maintain their position of dominance. This is why communists and anarchists have historically been among the first targets of fascist violence, and the first to engage fascists in the streets and on the battlefield.

Materialist and class-based definitions

Clara Zetkin: Fascism

Clara Zetkin’s article “Fascism” was published in 1923, shortly after Mussolini had taken power in Italy in 1922. It represents one of the earliest attempts to define fascism in Marxist terms, and distinguish it from other forms of right-wing violence. Zetkin was one of the first to point out that fascism has its roots in the middle class, or what she calls the “petty bourgeoisie,” a group that doesn’t quite hold the wealth required to buy out entire political parties, but still benefits to some degree from private property and the exploitation of workers. This group is largely made up of small business owners, landlords, professionals, and former military personnel, who occupy a relatively privileged position compared to the working class.

Threatened by both declining profits and political instability, the petty bourgeoisie form the core of fascist movements, while often recruiting people from the lower classes to do their dirty work. Zetkin observes that fascists tend to position themselves as alternatives to socialist or communist parties, presenting themselves as a movement “for the people” while at the same time violently targeting society’s most vulnerable groups. Because of their willingness to attack leftist and working-class movements, who are their main political enemies, they often receive funding and support from the capitalist class, who find themselves increasingly relying on fascist groups in order to maintain the sputtering capitalist system during an economic crisis.

Leon Trotsky – Fascism: What It Is and How To Fight It

Leon Trotsky’s “Fascism: What It Is and How To Fight It” is a compilation of texts written mostly in the 1930s, during the rise of fascism in Germany. For Trotsky, as for Zetkin, the rise of fascism represents an important shift from “business as usual,” signalling the inability of liberal democratic institutions to keep order as the capitalist crisis intensifies and inequality skyrockets. As he puts it,

At the moment that the “normal” police and military resources of the bourgeois dictatorship, together with their parliamentary screens, no longer suffice to hold society in a state of equilibrium — the turn of the fascist regime arrives. Through the fascist agency, capitalism sets in motion the masses of the crazed petty bourgeoisie and the bands of declassed and demoralized lumpenproletariat — all the countless human beings whom finance capital itself has brought to desperation and frenzy.

Clara Zetkin, “Fascism,” Labour Monthly (August 1923): 69-78.

In Trotsky’s view, fascism emerges thanks to the conditions created by capitalism itself, which gives rise to inequality and precarity by concentrating wealth in fewer and fewer hands. However, he also points out that there is nothing to guarantee that members of the middle class will automatically turn to fascism, and instead suggests that they can also be won over to the Left, assuming the Left is organized and effective in winning concrete material gains for the majority. To do this however, the Left must not only contend with the fascists, but also the capitalist class, who would, given the choice, prefer to see fascism come out on top.

Michael Parenti: Blackshirts and Reds

Blackshirts and Reds: Rational Fascism and the Overthrow of Communism by Michael Parenti also explains fascism in terms of class struggle, noting that the primary function of fascism was the violent suppression of communists, socialists, trade unionists, and other leftist groups and organizations, which, at the time of fascism’s rise in Europe, threatened to overthrow capitalism and the ruling capitalist class. In contrast to ahistorical accounts which attribute fascism’s growth to the unparalleled charisma of Hitler, Mussolini, or other fascist leaders, Parenti argues that fascism came to power in large part thanks to the cooperation and material support of the financiers and industrialists, who benefited from and encouraged the fascists’ unrelenting attacks on the anti-capitalist Left.

Parenti makes it clear that the conflict between the Left and the Right isn’t the result of a simple misunderstanding or mass delusion; rather it originates from real social contradictions. Leftist movements do represent a challenge to the established social order. For those who derive at least some benefits from capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy, imperialism, and other systems of domination and oppression, fascism can thus seem like a perfectly rational and reasonable option, allowing them to hold on to their position of privilege in the short term, even if most of them will wind up being betrayed by the movement in the long run. Fascists can never actually deliver on their promise of a return to an idealized past, since that past never existed in the first place. The best they can offer are privileges for a select few at the cost of imperialist expansion, war, and genocide. The alternative, of course, would be to join other oppressed groups in challenging the rule of the capitalist class, a path which is almost unthinkable to generations that have grown up with a culture that is severely allergic to any discussion of class. As Parenti makes clear throughout his book, anti-communism and the suppression of Marxism have resulted in a situation where fascism appears to be the only viable option for those who are frustrated with the status quo. If disillusioned white men are so quick to jump on the anti-leftist, anti-feminist, and “anti-anti-racist” bandwagons, it may have more to do with the way our society is currently structured than with the special cunning or sophistication of far-right organizers.

Robert Paxton: The Anatomy of Fascism

Robert O. Paxton’s The Anatomy of Fascism follows a similar route as Parenti and Trotsky, attempting to explain what fascism does, not just what it says. The book traces fascism’s development through the 20th century, focusing especially on Italy and Germany. Paxton breaks down this development into five stages: “(1) the creation of movements; (2) their rooting in the political system; (3) their seizure of power; (4) the exercise of power; (5) and, finally, the long duration, during which the fascist regime chooses either radicalization or entropy.” Paxton also works to underline “the complicity of ordinary people in the establishment and functioning of fascist regimes,” suggesting that the extreme violence of events like the Holocaust had its origins, not in the minds of deranged monsters, but in the day-to-day routines and banal choices of “members of the establishment: magistrates, police officials, army officers, businessmen.”

For Paxton, there is no “fixed essence” of fascism, only a “a series of processes working themselves out over time.” In other words, fascism must be understood historically, as a movement involving many different parts, not simply as a static, self-contained thing or set of ideas. As he notes in the introduction to his book, the idea that fascism is an ideology, first and foremost, is a view promoted by fascists themselves. This serves as a kind of trap, leading us to focus on their doctrines or propaganda, while neglecting the material and social conditions that accompany their emergence and rise to power. It also allows contemporary fascists to present themselves as harmless or at the very least deserving of constitutional protection—after all, they argue, it’s just “ideas,” and everyone is entitled to their ideas. Fascism privileges idealism over materialism, and expression over structural change. As Walter Benjamin famously puts it in the epilogue of “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,”

Fascism attempts to organize the newly created proletarian masses without affecting the property structure which the masses strive to eliminate. Fascism sees its salvation in giving these masses not their right, but instead a chance to express themselves. The masses have a right to change property relations; Fascism seeks to give them an expression while preserving property.

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 19.

Paxton’s account is particularly useful for three reasons. First, it helps to highlight the contradictions between fascist rhetoric and practice, using historical examples. For example, he argues that despite an early commitment to anti-capitalism, fascist parties, once in power, mostly failed to act on their promises to the working class, as this would have alienated their wealthy supporters. Secondly, it helps to demystify fascist movements, and suggests the need for different strategies and approaches that correspond to different stages of development. Dealing with Nazis in power is a very different thing from dealing with Nazis who are just beginning to build a mass movement. Third, it underlines the fact that fascists do not come to power on their own, but rely on building coalitions with established conservative and liberal forces. This presents an opportunity for anti-fascists, who can apply pressure on centrist organizations and parties that are concerned with preserving their public image, making it clear that any alliance with fascist groups or politics will not be accepted by the public at large.

Some important additions

Zak Cope – Divided World, Divided Class

Despite the strengths of the previous texts, none of them devote much time to analyzing the origins of racism and white supremacy within fascist movements—a serious oversight given the role white supremacy has played in the historical development of many fascist organizations and regimes. Zak Cope’s book Divided World, Divided Class: Global Political Economy and the Stratification of Labour Under Capitalism focuses on the ties between racism and imperialism, and the creation of what Marxists call the “labour aristocracy,” a relatively privileged segment of the working class that lives in rich, imperialist countries and benefits from the unusually high profits (also known as superprofits) extracted from the Global South. Cope suggests that it is the global division of labour created by imperialism which, above all, accounts for the spread of racist ideology. As he states,

Racism does not occur within the confines of a hermetically isolated society, but within an international class system fundamentally structured by imperialism. The ethnic, ‘racial’ or religious composition of especially oppressed sections of the First World working class is intrinsically related to the geographic, military, legal, cultural and economic mechanics of imperialist national oppression.

Zak Cope, Divided World, Divided Class: Global Political Economy and the Stratification of Labour under Capitalism (Montreal: Kersplebedeb, 2015), 5.

In other words, racism can be understood as an ideology that legitimizes imperialism and the creation of an uneven division of labour where the worst, most brutal forms of work are reserved for the people of colonized countries. It’s the racialized people of the Global South who produce most of the world’s commodities, which are then sold to the wealthier, majority-white residents of the imperial core, who maintain a quasi-monopoly over the best paid and least back-breaking forms of labour. The higher wages paid to workers in the Global North are made possible by the slavery and starvation wages imposed on colonized people, producing superprofits for corporations based in countries like the US and Canada, some of which are directed back to the state through taxes in order to pay for our social services and infrastructure. The reason we are so well off with respect to workers in other regions isn’t because we are especially good at fighting for our rights or wrenching capital away from the hands of capitalists, but because we are part of a global system that siphons wealth away from the periphery and towards the core. This makes it easier for capitalists to give up a portion of their earnings to reduce social tensions at home, while still maintaining a healthy rate of profit.

Racism works to naturalize this global division of labour. Instead of seeing global inequality as a product of history and the capitalist drive towards profit, we are encouraged to believe that white people are inherently superior, and that this is why countries inhabited largely by non-whites are so “underdeveloped.” The fact that imperialist powers played an active role in underdeveloping colonized countries, by stripping them of their resources, fighting any attempt at self-determination or autonomy, murdering large numbers of people, and enslaving the rest in mines, plantations, prisons, and factories, is either downplayed or ignored. Instead, the people living in these countries are blamed for the violence, corruption, and poverty caused, to a great extent, by Western powers.

This pattern of racist scapegoating has recently crystallized in the image of the “migrant,” a shadowy, heavily racialized figure who has no distinct country of origin, but is nevertheless assumed to be black or brown and probably Muslim. In both the mainstream media and far-right propaganda, the migrant is portrayed as a criminal, a parasite, and a threat to Western civilization itself. As Yasmin Jiwani writes, drawing on the work of Teun A. van Dijk, “when the media report on issues of immigration, they invariably cite figures indicating how many of them are out there, and how many more are trying to get in,” invoking an image of “invasive hordes that need to be contained and controlled.” In essence, the West projects all the violence it has inflicted on the rest of the world onto the bodies of those it has harmed. Images of refugees approaching the border are viewed with horror, like ghosts that have come back to haunt the imperialist core. The attempt to banish the migrant, both figuratively and through policy measures and the construction of militarized borders and concentration camps, becomes a way of rejecting any awareness of or responsibility for the centuries of imperialism that underlie First World privilege, and continue to drive the so-called “migrant crisis.”

As Cope remarks, it’s no coincidence that fascism first took root in Europe, the heartland of imperialism and colonialism, near the end of the First World War, when imperialist expansion was nearing its geographic limits, forcing the imperial powers to battle one another for control of the colonies. The extreme nationalism that marked the early fascist movements of the 20th century, and which persists today, is a consequence of the conflict of interests, not just between the Global North and the Global South, but also between rival imperialist nations, whose fortunes depend on competing with one another for unhindered access to the labour and resources of the colonies. Fascism, as it turns out, found its most fertile ground among the losers of this competition. As Cope notes, quoting the political scientist Richard Löwenthal:

Fascism exemplifies the imperialism of those who have arrived late at the partition of the world. Behind this imperialism lies a huge need for expansionary opportunities, but none of the traditional weapons for realising them. It is a form of imperialism which cannot operate by means of loans, since it is so much in debt, nor on the basis of technical superiority, since it is uncompetitive in so many areas. It is something novel in history—an imperialism of paupers and bankrupts.

Richard Löwenthal, “The fascist state and monopoly capitalism,” in Marxists in Face of Fascism, ed. David Beetham (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1983), 338-9, quoted in Cope, 296.

This argument aligns with Robert Paxton’s definition of fascism as “A form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy and purity,” as well as Josephine Armistead’s claim that “the fear of humiliation [lies] at the root of fascism.” Fascism is the movement of temporarily embarrassed millionaires, of people for whom the desire to join the ranks of the imperialist elite outweighs the desire to work together to build a more just and humane society. While fascists themselves may not recognize it, the hatred they direct against immigrants, Indigenous people, Black people, and other colonized groups, combined with their promotion of “patriotism” and nationalism, all work to reinforce the global division of labour, at the expense of the international working class.

As Cope puts it, “geographically speaking, on its own soil fascism is imperialist repression turned inward.” When the imperialist core reaches the limits of its ability to extract wealth from overseas, it begins to eat itself, imposing the same hardships on certain portions of its people that it had originally applied to the colonized subjects of the Global South. For privileged white Europeans and North Americans, what is so shocking and disturbing about this process isn’t the unique brutality of fascism—because it is not in any way unique. Rather, fascism is horrifying because it takes the dehumanizing violence that tends to happen far away, or behind closed doors, and brings it home, laying it bare for everyone to see. To quote Aimé Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism,

What [the white man] cannot forgive Hitler for is not the crime in itself, the crime against man, it is not the humiliation of man as such, it is the crime against the white man, the humiliation of the white man, and the fact that he applied to Europe colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved exclusively for the Arabs of Algeria, the ‘coolies’ of India, and the ‘niggers’ of Africa.”

Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, trans. Joan Pinkman (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 1972), 36.

Josephine Armistead – The Silicon Ideology

Josephine Armistead’s recent works, “The Silicon Ideology” and “The Silicon Ideology Revisited,” published in 2016 and 2017 respectively, provide a helpful counterpoint to Nagle’s assessment of the Alt-Right. Unlike Nagle, Armistead draws a direct connection between the Alt-Right and earlier fascist movements, while also providing a helpful breakdown of various theoretical approaches to fascism. After surveying the literature on fascism, she dives into the historical origins of neo-reaction, a 21st-century variant of fascism that combines calls for an authoritarian form of government (transforming the country into either a joint-stock corporation or a monarchy run by tech CEOs like Elon Musk), with ethnic nationalism, scientific racism, extreme misogyny, transhumanism, and absolute faith in the power of technology. According to Armistead, “There are two poles within neo-reaction, the ‘academic’ pole, exemplified in LessWrong and the blogs of the main theorists of the movement (Unqualified Reservations, More Right, Outside In), and the ‘alt-right’ pole, exemplified in 4chan (especially the /pol/ board), 8chan, My Posting Career, and The Right Stuff.”

For Armistead, the origins of the Alt-Right lie in Silicon Valley, and the rise of a technocratic elite that has all but abandoned the communal ideals of early hacker cultures (which emerged in an environment where computer technology had not yet been fully commodified), in favour of an entrepreneurial spirit of individual empowerment. The title of her essays evoke Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron’s influential article “The Californian Ideology,” which describes the fusion of American libertarianism, technological determinism, 1960s counterculture, and reactionary neoconservatism that emerged alongside the growth of Silicon Valley and the dotcom bubble in the 1990s. In contrast to the stereotype of the dim-witted, blue collar neo-Nazi skinhead, neo-reactionaries present themselves as tech-savvy, white collar intellectuals. The extreme concentration of power and capital in Silicon Valley, combined with the fallout of the 2008 financial crisis, climate change, and the “War on Terror,” has helped drive fascism into the 21st century.

Summing Up

To summarize, I would like to argue that the following points are essential for building a full-fledged understanding of fascism:

- Fascism is a mass movement that emerges in periods of capitalist crisis, when liberal democratic institutions begin to collapse or can no longer maintain order

- Fascism has its base in the middle class, which includes both the petty bourgeoisie (small business owners, professionals, landlords, etc.), and the labour aristocracy, i.e. the portion of the global working class that benefits from imperialism

- Fascism is primarily a reaction to a loss of privilege, including threats to the existing social order caused by capitalist crisis and the rise of anti-oppressive movements from below

- Fascism seeks to re-entrench existing hierarchies by terrorizing marginalized people and crushing the Left

- Fascist movements often receive aid from the capitalist class, or their representatives (for example, the police, or established political parties); for the capitalist class, fascism is preferable to allowing the anti-capitalist Left to take power

- Fascism involves ideology but cannot be reduced to it; fascist talking points and symbols are often appropriated from the Left, but stripped of their political foundations, resulting in contradictions between rhetoric and practice

- Fascism can be seen as a product of the various interwoven forms of oppression that exist in capitalist society; while fascists may try to overthrow the sitting government, they don’t present an existential threat to the global economic system as a whole, rather they are its last line of defence3

Footnotes

- The fact that some of the most misleading definitions of fascism are also among the most popular is not an accident, but a reflection of the dominant interests in our society. It’s in the best interests of the capitalist class to disguise the origins of fascism, which is why it’s crucial to approach the literature on the topic with a critical eye.

- It’s worth noting that high birth rates have instead morphed into a source of racist moral panic, particularly among rich and middle class whites who see high birth rates in the periphery, as well as among indigenous groups, as a threat to their social dominance and their ability to maintain a relatively luxurious lifestyle. This has resulted in renewed pressure on white women to procreate, not in order to provide workers for factories, but in order to ensure “the future of the white race.” For pro-choice white liberals, on the other hand, the fact that they have few children is seen as a sign of moral superiority, and a license to police the bodies of women of colour, while devaluing the lives of their offspring. For more discussion on this issue, see: Betsy Hartmann, “Conserving Racism: The Greening of Hate at Home and Abroad,” Different Takes, no. 27 (Winter 2004).

- The full dissertation that this excerpt is drawn from, along with more extensive citations, can be found here.