Reblogged from: http://thetreehouse.ghost.io/treating-women-with-respect/

This is a (partial) guide for any men who want to build considerate and respectful relationships with women. If you think you already know how to do that, you should probably read this anyway (especially point #11) since a) it never hurts to have a refresher, b) you might be surprised by some things and, c) you can then make an informed decision about whether or not to recommend this guide to other men. A lot of men who consider themselves to be feminists still unintentionally engage in behaviours that hurt and marginalize women. This may be due in part to the fact that a lot of feminist discussions assume that people already know “the basics”–they have to, or else we would spend all of our time repeating ourselves. However my experiences, which are based mostly on working in academic and game-related communities, suggest that a lot of things that seem basic on the surface tend to be overlooked, particularly when they’re expressed in a more subtle fashion.

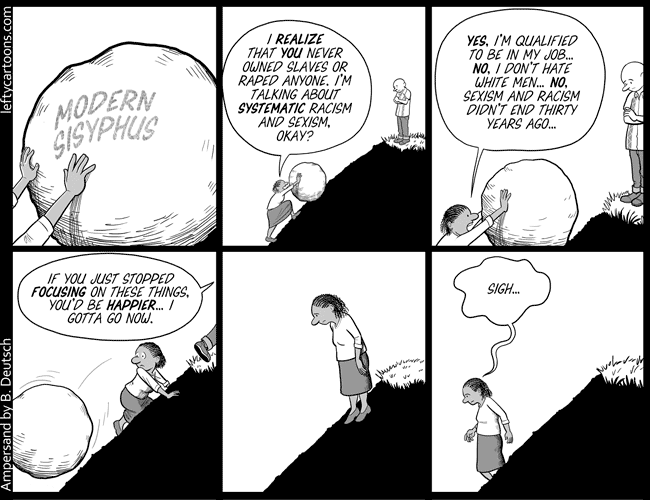

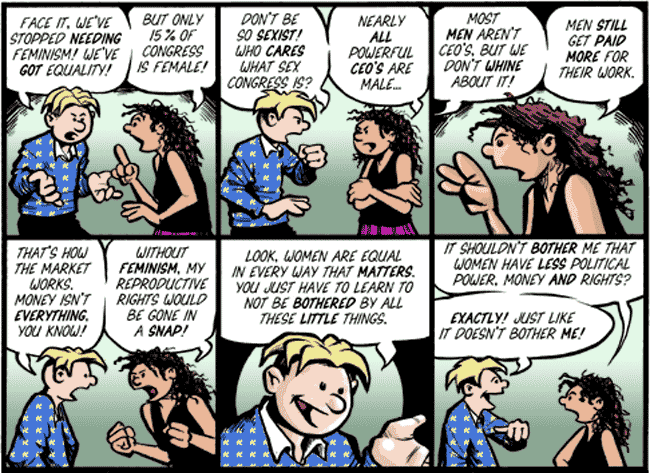

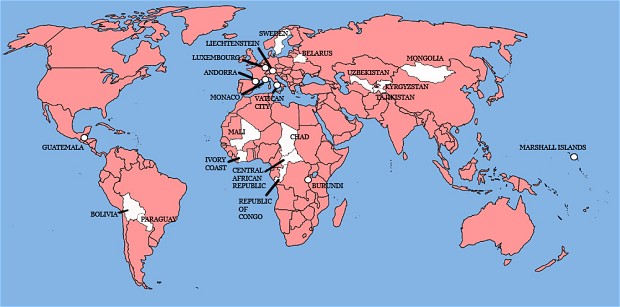

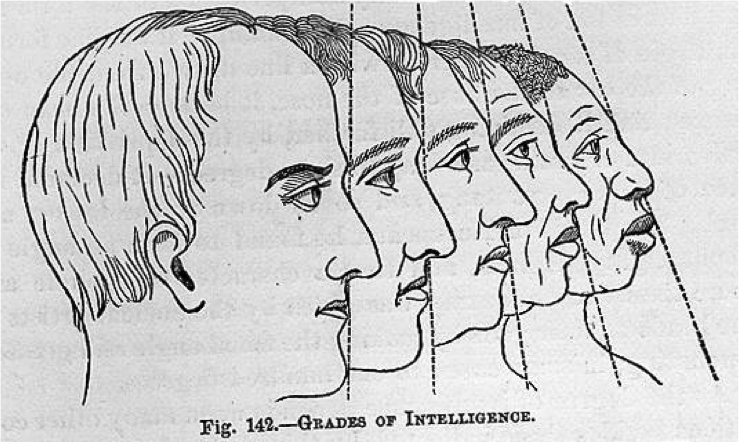

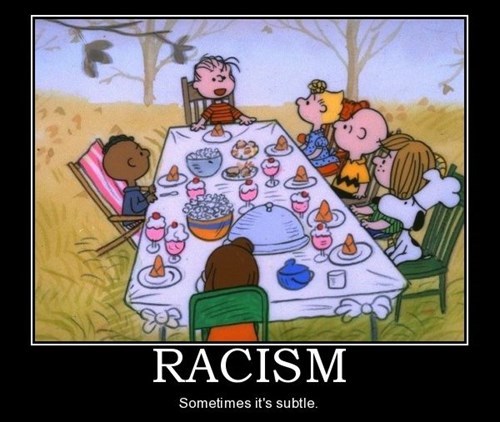

Subtle sexism is, in some ways, harder to tackle than the obvious stuff–like the use of sexist slurs, sexual assault, or refusing to let women vote–because it’s almost invisible to people who aren’t on the receiving end. This “death by a thousand cuts” still has a huge effect, however, on women’s lives. It also impacts men, who often don’t understand why women react in the ways that they do to behaviour that seems perfectly harmless to them. This guide is intended to help address that gap in understanding, although it should be understood from the get-go that it’s very incomplete and not without lots of caveats, exceptions, and exclusions. With that in mind, the first step to creating respectful relationships with women is…

1. Give women space to talk and make sure you listen when they do

Listening is a highly under-appreciated skill. It’s also a skill that is absolutely crucial to building a more just and equal world, not just between men and women, but across other categories of difference and oppression. Listening involves two steps, the first of which is learning to recognize when you’re taking up too much space by talking over others and not giving people an opportunity to respond on their own time and in their own ways. Sometimes that means letting go of that really smart remark that you’ve been dying to share, but it also means opening yourself up to lots of amazing insights that you might never have encountered otherwise. Remember to keep in mind that traditional gender roles designate men as the speakers and women as the listeners (despite the “chatty woman” stereotype), so there’s a good chance you’re underestimating how much the men in the room are talking, and overestimating how often women talk.

The second part is actually listening, especially when the person is saying things you don’t really want to hear, either because you disagree or because they’re being critical of you or your actions. The moment you start to feel defensive in a conversation is the moment that you should be turning the “listening dial” all the way up, because that’s when you’re most likely to learn something new. Also keep an eye out for gestures, shifts in vocal tones, and other social cues. Is the person you’re talking to displaying any signs of discomfort around you, such as nervous laughter? Are they looking away frequently and avoiding eye contact, or shuffling and fidgeting? It’s ok if you have trouble reading these kinds of signs; staying attentive and checking in verbally if you’re unsure about something can still help to create a safer environment.

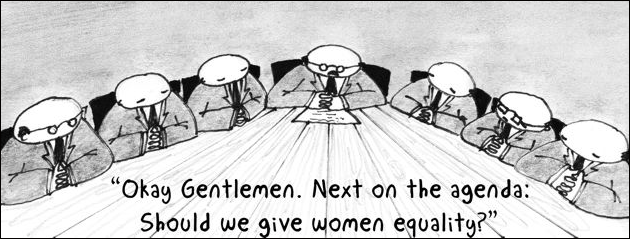

In some cases the safest way for women to deal with certain issues is to create a space of their own, outside the presence of men. If the idea of women meeting on their own is frightening or if it makes you feel angry or excluded, you might want to think long and hard about why you have so little trust in women operating outside the supervision of men. You might also want to think about why you feel entitled to that space, given that there are lots of spaces where women can’t go, either because of an explicit rule, or because the conditions in those spaces are unwelcoming and unsafe for them. Rather than challenging the need for such a space or accusing them of being “divisive,” allow women to make their own decisions about what they do or don’t need.

2. Be prepared to take “no” for an answer.

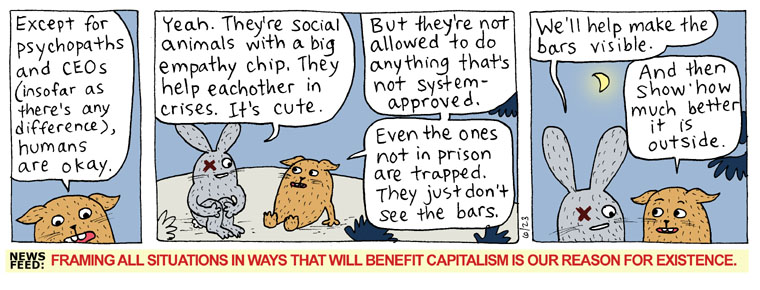

This is absolutely key, and something that a lot of people still struggle with. Rejection can be painful, and for a lot of folks the most “natural” response is to lash out against the person who rejected them. Unfortunately men are often encouraged to behave this way through subtle cultural signals and cues, which teach them that their masculinity, and thus their self-worth, hinges on their ability to assert dominance over others, to demonstrate persistence in the face of adversity, and to not take “no” for an answer. For example, think about the ways that male athletes, entrepreneurs, generals, and superheroes are often portrayed. Women, on the other hand, are taught to view persistent, non-consensual behaviour as “romantic,” and a sign of men’s dedication, confidence, strength, and overall superiority (Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey are well-known examples). These gender norms are incredibly harmful, creating an environment where care and consideration for others are viewed as a sign of weakness–something to be avoided at all costs–while violence and domination are glorified and celebrated.

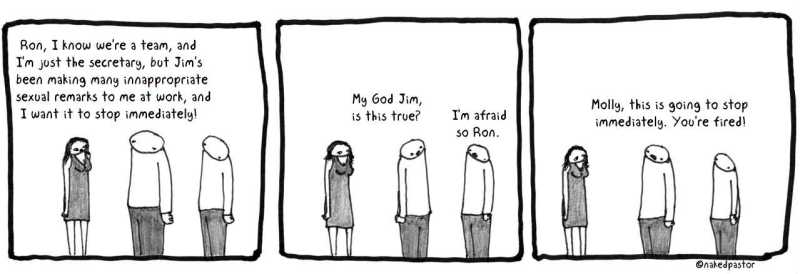

It also makes consent impossible, because it’s not consent unless the person giving it is free to say no, without repercussions. You may think you’re asking someone for their consent, but if your response to their “no” is to scream at them, shun them, insult them, fire them, or physically attack them, then you aren’t really giving them much of a choice in the matter. The fact that this sort of response is what many women expect when a straight man propositions them should give you an idea of just how common this sort of behaviour is, even among men who declare themselves feminists. It should also tell you something about why women will often give a noncommittal, half-hearted response rather than a direct no, because a direct no is too risky, especially if the woman is also poor, racialized, trans, dealing with a mental illness or disability, is a member of a stigmatized religious minority, or is otherwise disempowered. Which leads to the next point…

3. Don’t get mad at women for “failing to communicate” their needs or expectations.

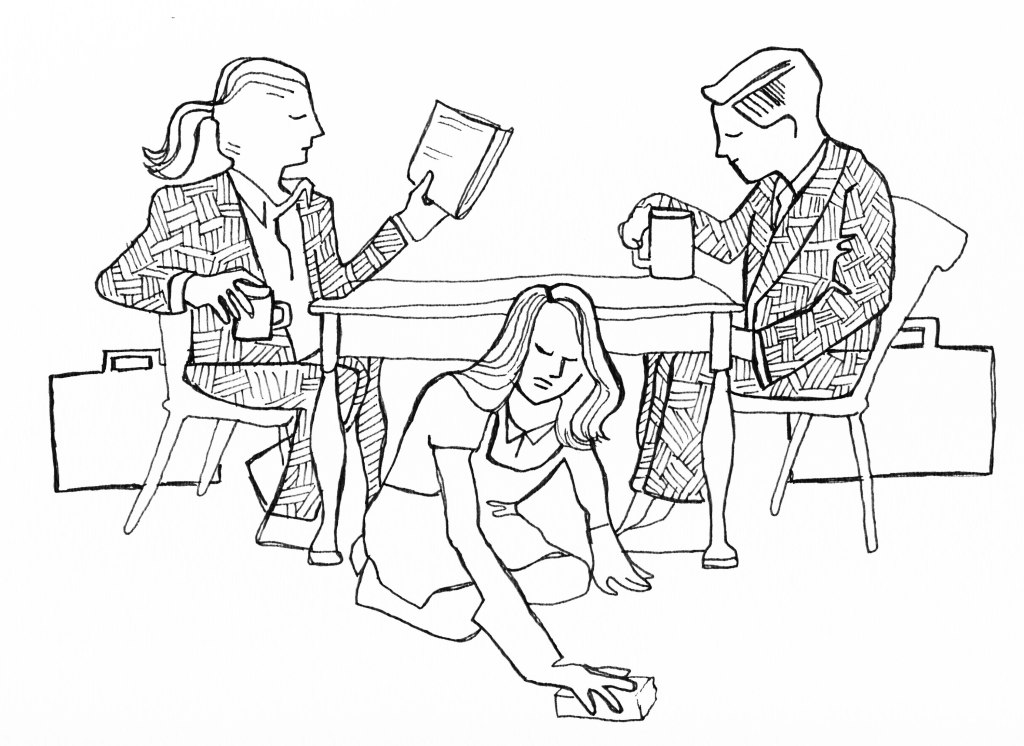

The important thing to remember here is that women are often punished for communicating their needs. Sometimes the punishment is subtle, for example when a woman complains about how she’s being treated by her male colleague and is immediately told that she’s being “too sensitive,” or is questioned about minor details by people acting under the assumption that she’s unreliable, and is probably making things up. Sometimes it’s more overt, like when women talk about feminist issues online and receive death threats and doxings in return. In other cases, their concerns are heard, and then promptly ignored, which is disempowering and a form of punishment all on its own, since it’s the equivalent of saying that that women’s needs and safety are unimportant. Regardless, the result of this repeated punishment is that many women are either afraid to speak up or, perhaps even worse, are convinced that whatever problems they face are their own fault, a result of their personal failings rather than external factors that are outside of their control. In a lot of cases, women will simply “suck it up” and bear it, even when someone is being abusive towards them. When the behaviour becomes unbearable, they’ll leave the space (if they can), rather than raise a complaint and risk repercussions, sacrificing a lot of opportunities, and personal or professional connections, in the process.

If a woman isn’t communicating with you, there’s probably a reason. It may be because of your personal behaviour, or it may be because of the factors described above. In any case, the best way to deal with it isn’t to punish the woman for “misleading” you, but to think about how you can contribute to creating an environment where that woman feels comfortable being direct and upfront with you. No one owes you their trust, regardless of your relationship to them. Trust is something you have to earn, and insisting otherwise reveals a sense of entitlement to someone else’s time, as well as their private feelings and experiences. In other words, it’s just another way of asserting control and domination over others.

4. Don’t insist that women explain sexism to you.

There are lots of resources available online that will help you understand how sexism and other forms of oppression work. In many places there are also workshops and community organizations that are focused on educating people about these issues, and can help you find resources. If you see a woman talking about her personal experiences with sexism, don’t jump in and demand that she explain to you how and why it’s sexism. Chances are this is something she’s had to explain a hundred times before, and it’s exhausting having to repeat the same lines over and over and over again, especially when you suspect that the person asking isn’t really listening to you, but is instead looking for a way to prove you wrong. A lot of the time these questions about why something is or is not sexist are asked in bad faith, because the person asking has already made up their mind. This unfortunately impacts men who genuinely don’t understand what’s going on, since women are less likely to respond to them. This isn’t the fault of the women however, but rather of all the people that have tried to derail their conversations about sexism, questioned their personal experiences, and punished them for speaking up. Rather than forcing women to explain sexism to you and then getting angry at them when they refuse, try doing the research yourself.

5. Don’t make her responsible for the harm you cause.

It’s ok to make mistakes, everyone does. What matters is how you respond when someone calls you out. If you fuck up and hurt someone, take responsibility for your actions, rather than placing that burden on the person you’ve hurt. This applies to everyone, but it’s particularly important when you’re in a position of power in relation to the person that you’ve hurt, and when the critique is specifically about how your actions reinforce that relation of power (for e.g. when a man is sexist towards a woman, when a white person is racist towards a non-white person, when a cisgender person is transphobic towards a trans person, etc.). Some general guidelines include:

Don’t make false apologies like “I’m sorry that you’re offended,” which shifts the blame and the focus of the conversation from your actions to their reactions.

Don’t insist that the person you’ve hurt is “overreacting,” or that they “misunderstood” your intentions. Your intentions aren’t what’s important—even the most well-intentioned people can cause a lot of harm. What’s important is the impact of your actions.

Don’t try to turn a critique into a personal attack on you and your morality. Again this is just another tactic for shifting responsibility onto the victim, while insisting that only people who can be proven to have “bad intentions” (i.e. virtually nobody) can be criticized. Chances are it was extremely difficult for the person criticizing your behaviour to even raise the issue in the first place. By arguing that they’re just trying to shame you or make you look bad, you’re actually implying that they’re the one at fault, making it more likely that they’ll keep silent the next time something bad happens to them.

6. Treat women as potential friends, colleagues, and fellow human beings first, everything else comes second.

Just because you’re attracted to a woman doesn’t mean this is the only way you can or should relate to her. Keep in mind that a lot of women are used to being treated as potential sexual partners, or “conquests,” first and foremost, while everything other than their physical appearance is either ignored, or else exploited in an effort to “win them over.” As soon as men discover that these women aren’t available for dating or sex, they suddenly lose interest in talking to them. This can be a pretty disheartening experience when it happens over and over again, particularly since women are taught–through everything from Snow White to cosmetic ads–that their main source of value lies in their ability to attract and please men, a lesson that is repeatedly reinforced by these sorts of experiences.

To avoid unintentionally playing into the sexual objectification of women, try to be conscious of how your level of attraction to a woman affects your behaviour. Are you more polite or friendly with women that you find attractive? Are you ignoring qualities about them that are more relevant to the given context, such as their professional background or technical skills, while paying undue attention to their physical appearance? Why? Would you be acting any differently if they were men? Note that casual sex and respect for women aren’t mutually exclusive. Just because you don’t want a long-term relationship, doesn’t mean they’re less deserving of your respect and consideration.

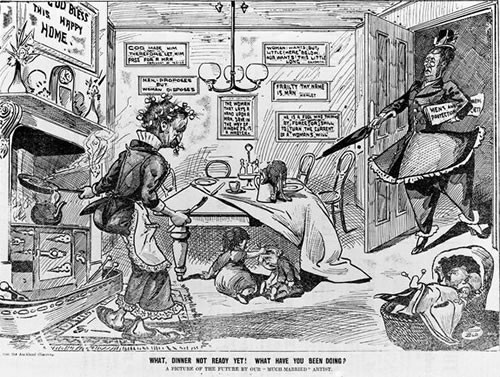

7. Don’t dismiss her just because she presents in a feminine way or likes “feminine” things.

Many of the things that are coded as “feminine” are also seen as less serious, frivolous, unprofessional, or juvenile. Sparkles, frills, ribbons, jewelry, the colour pink, cute stuffed animals, and cheerleading are all examples. The additional layers of meaning that these objects and activities have is partly a result of embedded sexism, and allowing those meanings to dominate your perception of the women who own or like them is essentially the same as viewing them through a sexist lens. The fact that a woman wears a lot of pink clothes with sparkles on them says absolutely nothing about her personal or professional accomplishments, her intelligence, or her ability to carry out “serious” tasks. The same goes for men and genderqueers who like feminine things or present in a feminine way.

8. Be careful with your compliments.

A lot of “compliments” that are directed at women aren’t really compliments, but rather a means of asserting control over them. They do this by making women feel obliged to show gratitude and acknowledge the person “complimenting” them, or else risk being punished by the man or their peers.

When the women suspects that the man complimenting them is attracted to them, but they don’t feel the same way, the simple question of if and how to respond can become a virtual minefield. On the one hand, they need to be extremely careful not to be too friendly with the guy, or they’ll be faced with more unwanted advances, and may be accused of “leading him on”–an interpretation that plays into the “seductress” and “slut” stereotypes. At the same time, they don’t want to be rude or come off as a “cold-hearted bitch,” another common stereotype, which could also escalate the situation or even lead to violence. As a result, women will sometimes feel trapped in situations that, from the outside, seem relatively harmless.

One way to avoid creating such a situation is to make sure that you get to know a woman before you compliment her. This will not only make your compliments more meaningful, since they’re more likely to be based on a real assessment of her strengths and interests than on some superficial feature of her appearance or her personality, but it will also give her a chance to assess where you’re coming from, and how you’re likely to respond to her actions.

Another possible way is to compare the compliment to one you would give a male friend or colleague. If the compliment sounds even slightly inappropriate to give a male friend or colleague, question why it seems appropriate to pay this compliment to the women you meet. Note that this thought experiment has its pitfalls, but is a good starting point when reflecting upon the comments and compliments you could make.

9. Don’t show up unannounced.

You might think that showing up at a women’s home or workplace is fun, casual, spontaneous, or “romantic,” but for many women this kind of behaviour is threatening and scary, particularly if they have been stalked, harassed, or abused in the past. By showing up without their permission, you’re signalling to them that they have no control over where or when they see you. If there is any uncertainty at all about whether or not it’s ok for you to come over without asking, even if you’re close friends and you’ve been to her place before, make sure you ask. Don’t assume it’s fine just because she “seems chill” or has been friendly with you in the past.

10. There’s no universal line for discomfort or distress.

These guidelines aren’t meant to apply equally to all women in all situations. Some women may be fine with you showing up at their place unannounced, while for others it could trigger a panic attack. The key is that you ask them first. Don’t assume they’re fine with it and then wait for them to tell you otherwise. Similarly, don’t assume that because one woman is ok with something, other women must feel the same way. Women all have different experiences and histories, and while there are definitely some common patterns that emerge, there are also countless variations and exceptions. Asking that someone spell out to you, in precise detail, a universal rule for when something is or is not ok is an impossible demand, since it depends both on the people involved and on the specific context. Power relations are tricky that way.

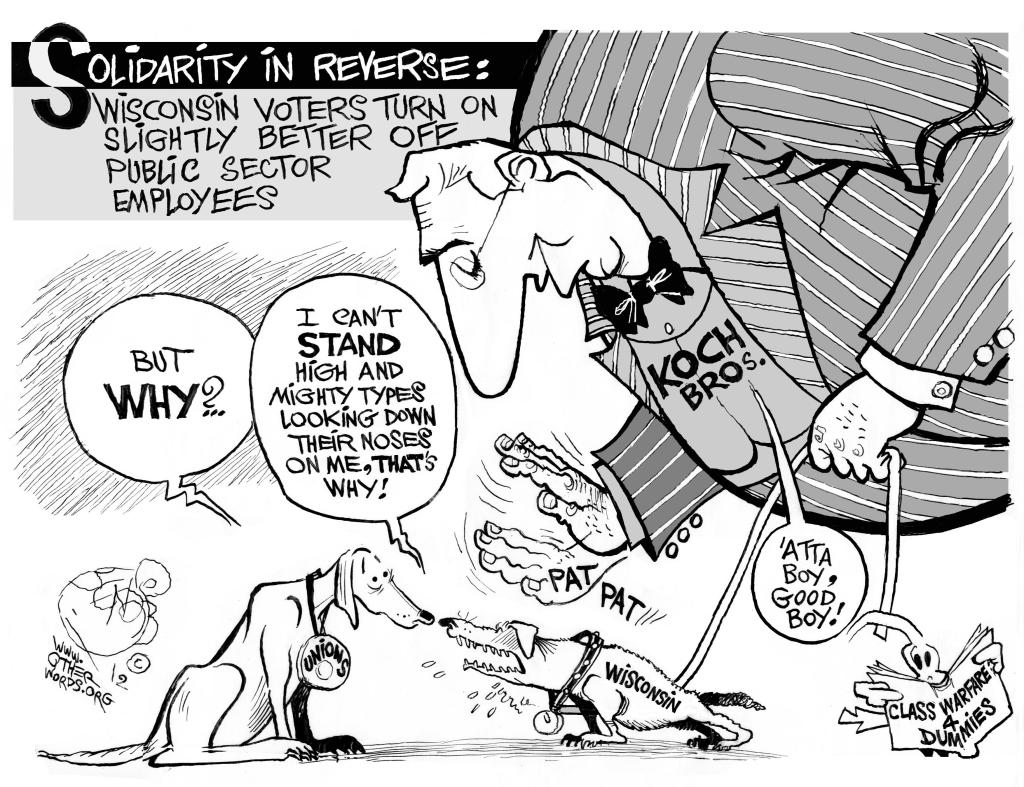

11. “Feminist” and “ally” aren’t badges for you to wear.

There’s nothing more frustrating than watching someone who claims to be a feminist or an ally use these words as a way to hog the spotlight or deflect criticism when they’re called out on oppressive behaviour. Ally isn’t a get-out-of-jail-free card or a badge you can wear to signal that you’re part of “the feminist club” whenever it’s convenient; it’s an approach or a way of acting in a given situation that is about transferring power to, and operating in solidarity with, the marginalized and the oppressed. What this means is that you don’t get to decide when you are or are not being an ally. It also means you need to be accountable to the groups that you’re trying to support. Just because you did something helpful for someone that one time doesn’t mean that you have now been branded an ally-4-life and are free to do whatever you want. Taking on oppression requires constant effort and is a never-ending learning process. If you think that you’ve already got it all figured out and have nothing left to learn, you’re probably doing it wrong. If you love to talk about how you’re an ally but haven’t actually done anything to change your behaviour, you’re probably doing it wrong. If your response to being told that you’re doing it wrong is to shut down the discussion or “quit”… well you get the idea. Yes it can seem like a lot of work, but just remind yourself how much harder it must be for the people who are part of that oppressed group, because they don’t get to choose whether or not to care about their oppression, they live with it every day.

Thanks to everyone that helped me put this together.